Unless you’ve been living in a cave, you’ve no doubt heard that a few days ago, another celebrity lost his battle with addiction. Philip Seymour Hoffman was only 46 years old. A year older than me. He was found with a heroin needle still in his arm.

Today, I read a blog post in response to his death written by a recovering addict. By the end of it, I was in tears. Not just because of how beautifully written it is, but how big the problem is. It’s a very frank, very simply put view of what addiction really is. How it works. And why people like Hoffman, who had the world by the balls, succumb to it.

I urge you to read it now, especially if you don’t deal with the demons of addiction. It gives a new, painful perspective on things from someone who lives daily with those demons. If you are an addict, I urge you to read it now, too. As the friend of mine who posted it said, “It reminds me not to be complacent in my choice of sobriety.”

Addiction, Mental Health, and a Society That Fails to Understand Either by Debie Hive

The part that struck me is where she says this:

The only way to really deal with addiction is one that is multi-faceted, one that makes us uncomfortable. It is messy and complicated and takes a lifetime of effort. It involves relapses and second chances and third chances. It involves support, sometimes sponsors. It involves therapy and counseling until whatever the root cause is has been revealed and addressed. It involves consideration of not just the physical withdrawal, but the emotional withdrawal, the social withdrawal, the psychological withdrawal. It involves a mental health system with adequate resources. It requires support instead of judgement.

And sometimes, even when all those things exist, it fails. It fails because addiction can take people and swallow them whole. It can rob them of everything they value, everyone they love. It can strip them of everything they care about, rob them of reason and logic. It can convince them that they aren’t worthy, that they have failed not just themselves, but everyone else. It tells them that they are broken and irreparable. Then it shoves them back down and does it again.

As I read that post, and found myself tearing up at her words, I realized I wasn’t thinking about Hoffman, or drugs at all. But I understood completely what the demons are that she talks about. About having forces and compulsions inside you that rob you of reason and logic, that shove you down and swallow you whole.

I get that. I live with that, too. I would not DREAM of putting a needle in my arm because drugs aren’t my bag.

Food is. And it’s a long, painful, goddamn slow way of killing yourself.

Like addicts, fat people get looked at with pity. Scorn. Anger. Frustration. We are called weak. Losers. A waste.

We are fat for the same reasons addicts are high and alcoholics are drunk. We use food the same way they use drugs and booze. We eat instead of shooting up. We binge on donuts, not booze.

And I wonder if any other people like me who have had a lifelong battle with weight see the same parallels.

I think the reason this blog post resonated so loudly with me, even though I don’t deal with a drug or alcohol addiction is that a month or so ago, I saw part of a show on TLC called “My 600-Pound Life.” And the episode I saw followed a man on Guam named Ricky Naptui, who at his heaviest topped out at nearly 900 pounds.

900-Pound Man: The Race Against Time

Maybe it’s because I’ve been wrestling my own demons so hard over the past year that I was able to watch this show and see it from the point of view that I did. I didn’t look at Ricky with disgust. Or even pity, really. I did get mad at his doctors. What Ricky thought he wanted and needed was weight loss surgery that would make him lose weight. The problem with that is that in order to do the surgery, he had to lose hundreds of pounds, first.

If you eat yourself up to 900 pounds, it’s not like dropping a couple hundred is going to be a walk in the park. The doctors were approaching it from a purely physical and surgical standpoint. If you eat less, you will lose weight. If you lose weight, we will do a life-threatening procedure that has more complications than benefits to help you lose weight. Convoluted thinking at best.

NOT ONE PERSON ASKED RICKY WHY HE EATS.

Maybe they just assumed it was because he was a pig.

I’m sure it’s what they assume about me.

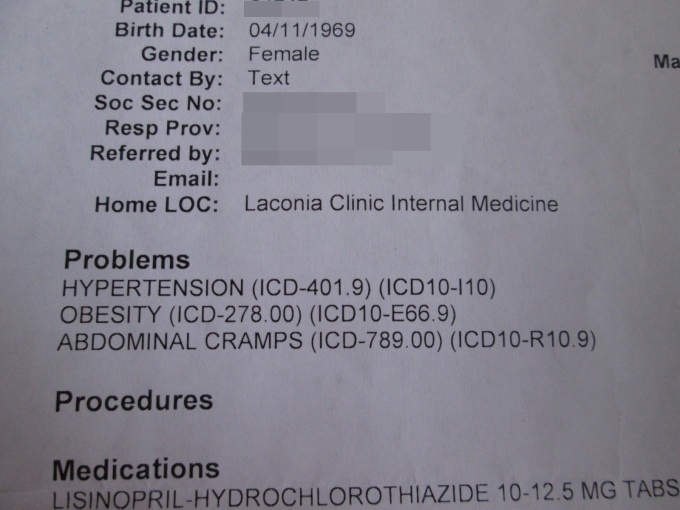

I use the present tense because I’m fully aware that at 226 pounds, I’m still obese. People who don’t know how far I’ve come see a fat woman, and that’s not an unkind assessment or self-deprecation. I still have at least 80 pounds to lose. That’s pretty fat, any way you slice it. I am fully aware that people look at me and have the thought cross through their mind that I should put my fork down and step away from the table once in awhile. Jesus, have some self-control.

They’re the same people, no doubt, who look at Philip Seymour Hoffman and say, “Jesus. Just don’t use drugs. How fucking hard is that?”

Fuck Forgive them, for they know not what they do.

So I watched as Ricky’s doctors expressed concern with what he eats, and how much. He needs to eat good food. He needs to eat less food. He needs to get him to the point where he can at least stand up unaided, which he could not do. They couldn’t get an accurate weight because he could not stand unsupported.

And the whole time they were telling him that he needs to lose at least 150 pounds on his own before they can consider surgery, I could see the frustration and desperation building in Ricky. He kept trying to find the words to tell them, “If I could lose that weight on my own, I wouldn’t need you. I wouldn’t be stuck in this bed. I can’t stop eating, and I don’t know why.”

But they talked over him. They cut him off. They were so concerned with pointing out the path he was going to have to follow that not one person took the time to listen to why that path seemed utterly impossible for him to even attempt.

And I wanted to reach into that TV and hold his hand and ask him why he eats. And listen to him. Because I know that helpless feeling. I know feeling scared. I know all about not understanding why you can’t seem to eat like normal people. And I know the pain of knowing how people look at you. The pity, the scorn, the disgust, the sadness. It’s demoralizing. And I know he just wanted someone to help, and the best way anyone could do that was by listening.

Only no one did.

Ricky died at the age of 36, and the cause of death listed was “morbid obesity.”

I didn’t immediately look at Philip Seymour Hoffman and think “There but by the grace of God go I.” But I looked at Ricky and I did. Ricky needed an angel. Someone to listen to him, to help him sort out his feelings. He needed someone to talk about food with him, and help him figure out what part it plays in his life and how he could work to change that.

But all they wanted to do was push him into a diet. They wanted to cut him up and hope for the best.

What Ricky needed was help with his addiction. He needed help with his demons. But as Ms. Hive pointed out in her blog post, our mental help resources are lacking. We want to be able to cure addiction with rehab or prison, and when those things don’t work, we are left with waiting for death to take them. In the same way, obesity isn’t solved with dieting or gym memberships or obsessively counting calories. It’s certainly not solved with surgery.

It’s solved with change, and that change happens inside your mind as much as inside your body. And it’s hard, and not everyone can do it alone. Hell, maybe no one can do it alone. I’m not doing it alone. I have an amazing support system who should get gold medals for getting me through this.

I have a best friend who listens to me without judging and only reminds me of the things I already know to be true. He offers me the reason and logic that my demons try to take away, putting back the bits that break apart from time to time when the battle leaves me damaged.

I have a husband who knows that he is the one person who can make me feel beautiful in this world at a time where my self-esteem is at an all-time low. He supports my efforts and puts up with me when the battle gets to be too much. He is my safe, soft place to fall.

I have a sister who knows what it feels like to have never been an athlete in her whole life, but has done the work to become one. She tells me that I am an athlete, too, reminds me that my daily workouts are training, and keeps me reined in when I get too far ahead of myself, and holds me up when I fear I’ve bitten off more than I can chew.

My support system grounds me and keeps me tethered to sanity. And I’m not exaggerating when I say that my sanity, my own sobriety, is tenuous at best. I have people to talk to. I have people who support me.

Ricky didn’t have that. His wife didn’t know what to do to help him. Hive says in her post, “Until you’ve had to tease out where the line between believing in someone and enabling them is, you can’t know what it is like.” She wanted him to be happy, but the only thing that made him happy was the thing that was killing him.

People who turn to food for comfort, for happiness, for friendship–we have a lot in common with addicts. We want to feel better, if only for a little while. Food helps us cope. And sometimes, the food just calls to us and we can’t stop eating, even when we want to. We hate ourselves for bingeing for no reason at all. We hate that we just can’t stop.

We hate ourselves for it.

We hate ourselves.

Much like drug and alcohol addiction, people with food issues habitually need more help than what we get. We don’t really need another diet plan. We don’t need another 7-minute workout. We don’t need another app for our phone. We certainly don’t need surgery, and we don’t need a magic pill that makes the fat go away.

We need someone to listen. We need someone to talk to us. To talk with us, not to us. We need professionals, from doctors, psychologists, therapists, and nutritionists who understand that the problem with our fat is not in our bodies, but in our heads, and if we work on sorting through our issues and get guidance with battling our demons, we can and will find a way to lose our weight.

And even if we get that help, there are no guarantees. Addicts relapse. Hoffman had been clean for 23 years before he relapsed. He was considered a sort of guru in AA because he helped so many other people. You can’t cure addiction. The fight never ends.

I know as well that this battle of mine will never be over. I fear relapse. I know people are watching me and seeing my progress and many don’t know what it takes for me to do this. If I fail, if I put weight back on, they won’t understand why. Some will. Or maybe some will just shrug and say “What a waste.”

There is hope. There are addicts who make it. There are people like me, and even heavier, who make it. I don’t believe I’m doomed to failure, but I know the odds are not in my favor.

It’s my hope that this fight gets easier at some point, but I kind of doubt it ever will. I’m not expecting it, or counting on it. I suspect it’s more likely that it will be as it has been for the past year: some hard stretches, and some easy stretches. Sometimes the demons will beat the shit out of me, but I’ll get back up, bruised, but stronger for the fight.

That thought is exhausting, to be honest, and after 23 years of it, I can see why a talented actor who had everything to live for put a needle in his arm.

He was tired. He was bruised. He was battered. He just wanted the demons to leave him alone, just for a little while.

Ricky never had a chance against his demons, because “the system”–whatever that is–failed him. Food was all he had, and in the end, it killed him.

There, but by the grace of God, go I.